My favorite artists are the ones that make me stop and wonder “How did they do that?”. How did a 21-year-old Bob Dylan write “Blowin’ in the Wind”? How did Robert Towne write the screenplay for “Chinatown”? How did Harper Lee write “To Kill a Mockingbird”? Some things are just impossibly perfect.

Modern Art, also referred to as Modernism (1860-1970), is another of those impossible things. Modernists were artists that rejected all traditional forms of art to include their personal perspectives and the consequences and effects of war and industrialization in the ever-developing, ever-changing contemporary world. Modernists assembled their masterpieces by experimenting with new techniques while disregarding old rules relating to color, perspective, and composition to create their own visions of how artworks should be constructed. Some people found modern art dangerous; some found it frustrating.

Rivalries can also be dangerous and frustrating, but they can also fuel great works of art. The most widely celebrated modernists elevated themselves to greatness because of a burning desire to out-do their contemporaries. Maybe that’s how the artists that make me ask “How did they do that?” do that. Here are my favorite modern artists, their masterpieces, and the rivals that drove them to become eternal legends.

____________________________________________________________________________________

-

Vincent van Gogh

(30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890)

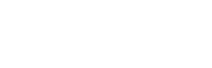

Anybody who knows me, knows who my favorite is. My favorite painter of all time is Dutch-born Vincent van Gogh – a failure who became an icon. An artist who only sold one painting that became one of the founding fathers of modern art. A man who lived his life in pain and torment but created the most beautiful and uplifting paintings ever seen on this planet. I’ve always said that one of the best things about art history (besides the artwork) are the stories. The tales of artist’s lives – their struggles, their triumphs, their origins, their final moments, their inspirations, and their legacies. Vincent van Gogh’s is the greatest story in the history of art. I love Vincent. The world loves Vincent and admires his unique style. If you look closely at his paintings, the brushstrokes are broken up. You can see each time van Gogh put his brush on the canvas.

Anybody who knows me, knows who my favorite is. My favorite painter of all time is Dutch-born Vincent van Gogh – a failure who became an icon. An artist who only sold one painting that became one of the founding fathers of modern art. A man who lived his life in pain and torment but created the most beautiful and uplifting paintings ever seen on this planet. I’ve always said that one of the best things about art history (besides the artwork) are the stories. The tales of artist’s lives – their struggles, their triumphs, their origins, their final moments, their inspirations, and their legacies. Vincent van Gogh’s is the greatest story in the history of art. I love Vincent. The world loves Vincent and admires his unique style. If you look closely at his paintings, the brushstrokes are broken up. You can see each time van Gogh put his brush on the canvas.

Vincent van Gogh, the eldest son of an upper-class Dutch minister was a quiet and thoughtful child who spent his days drawing. In his early adult life, he was kind of a screwup. His uncle got him a job in 1869 as an art dealer in The Hauge and in 1873 he was transferred to London. It was there that van Gogh fell in love with his landlady’s daughter but was rejected after confessing his love to her. He became very depressed and isolated and in 1875 his uncle arranged another transfer to Paris but was fired a year later because of his ever-developing poor attitude toward his employer. In 1876, he worked as supply teacher in a boarding school in London and then quit to become a Methodist minister’s assistant. At Christmas 1876, he returned home and worked in a bookstore in Dordrecht. He was unhappy in the position and immersed himself in religion deciding to become a pastor but he failed the University of Amsterdam theology entrance examination. He then failed a three-month course at a Protestant missionary school in Belgium. In 1879, he worked as a missionary in Belgium in a coal mining district where he often drew the coal miners but chose to live in a small hut and sleep on a straw floor. Because of his choice of an impoverished lifestyle, he was fired once again for “undermining the dignity of the priesthood”. He couldn’t do anything right. The only person who seemed to believe in him was his younger brother Theo who worked as an art dealer in Paris and often encouraged his brother to draw and paint. Theo would support his brother financially, emotionally, and spiritually for the rest of Vincent’s life. They would correspond with each other faithfully until Vincent’s death. He was a lifesaver.

In 1881, van Gogh returned home to his frustrated parents and began to draw and paint more frequently but in August he surprised his family by declaring his love to his cousin who also rejected his love and his marriage proposal. This rejection was devastating to van Gogh and drove him to The Hague to try to sell paintings and to meet with another cousin, Anton Mauve who took him on as a student in 1882. Mauve introduced him to oil painting and lent him money to set up a studio but after only a month of disagreements and arguments, the relationship ended. Soon afterwards, he began to paint with oils (paid for by Theo), he realized he loved the medium, spreading the paint liberally, scraping it from the canvas, and working it back with the brush. He wrote to his brother that he was surprised at how good the results were. He was hooked.

Van Gogh began his painting career in Neunen in The Netherlands in 1883 where he completed sketches and paintings of still lifes, weavers, cottages, and peasants in browns and other earth tones. During his two-year stay in Nuenen, he completed nearly 200 oil paintings culminating with his first major work “The Potato Eaters” in 1885. He asked Theo to help him sell his paintings in Paris, but his brother felt the earth tones were too dark and encouraged Vincent to paint in vibrant colors in the bright style of Impressionism. In late 1885, van Gogh moved to Antwerp where he lived in poverty renting a room above a paint dealer’s shop preferring to spend the money Theo sent every month on painting materials and models. It was here that van Gogh began to paint with bright reds, blues and greens. In 1886, he took the admission exam at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp and began to study studied drawing and painting with tuition paid for by Theo. He quickly got into trouble with the director of the academy and his teachers because of his unconventional painting style and argumentative attitude. In March, the academy decided that van Gogh had to repeat a year and, of course, he quit and moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo.

In Paris, van Gogh painted portraits of friends, still lifes and views of the Parisian skyline and cityscapes but he slowly began to dislike the crowded noise of The City of Lights. He slowly began to adopt elements of Pointillism, a technique in which small colored dots are applied to the canvas so that when seen from a distance they create an optical blend of complementary colors to form vibrant contrasts. He also began to realize that his health was slowly deteriorating. By 1887, the two brothers found living together almost unbearable and in early 1888, after having painted another 200 paintings during his two years in Paris, van Gogh left for the seaside town of Arles in southern France. It was here that he dreamed his greatest dream, when the masterpieces began to come, and where he had an almost fatal encounter with his rival.

After Paris, van Gogh began to feel guilty for living off his hard-working brother and wanted to find a way to support himself and his art career. His dream was to form an art colony in Arles – a home where a group of artists could live together sharing all funds made from sold paintings to pay for expenses. Van Gogh rented a yellow house (with Theo’s money) which became known as, coincidentally, and famously, “The Yellow House” and he flourished in Arles completing another 200 paintings of the countryside rich in yellow tones. He also began to earn the reputation as a madman and his neighbors began to take notice of his sometimes-eccentric behavior.

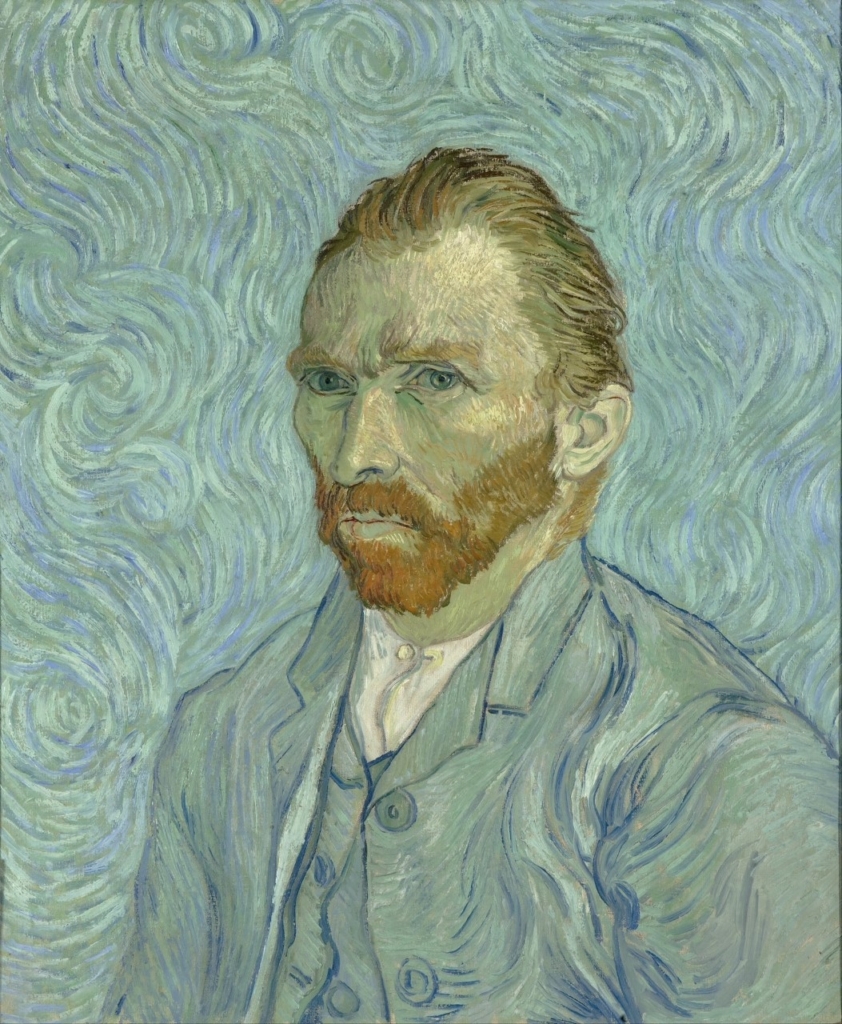

Vincent van Gogh, left, and Paul Gauguin.

Theo arranged for another painter to visit Vincent and entertain his idea of an artists’ colony – that artist was Paul Gauguin who van Gogh deeply admired. When Vincent heard this news, he became overjoyed, went out and purchased expensive furniture (with Theo’s money) and painted a series of paintings of sunflowers to hang on the walls of The Yellow House to welcome his new friend who arrived in October 1888. The rivalry between van Gogh and Gauguin began in friendship but that friendship rapidly deteriorated. They argued constantly. Gauguin, who was arrogant and entitled, tried to encourage van Gogh, who was humble and vulnerable, to paint using his imagination and to create art using what he sees in his mind – Vincent was adamant that true art is representational and that he can only paint what he sees with his eyes. Van Gogh greatly feared his new friend would leave him. Another failure. Another rejection. This tension resulted in a desperate chain of events two days before Christmas 1888 involving Gauguin storming out of The Yellow House after yet another argument, van Gogh chasing after him with a razor, Gauguin fearing for his life, van Gogh returning to their home and suffering a schizophrenic episode, then severing his left ear and giving it to a prostitute. Van Gogh was rushed to a hospital, Theo rushed from Paris to be by his side and Gauguin leaving Arles for good.

After a long hospital stay, van Gogh returned to “The Yellow House” but suffered from hallucinations, manic episodes and delusions of poisoning. In March 1889, his neighbors, who called him “le fou roux” (the redheaded madman), signed a petition to expel him from the town. With nowhere else to go, he voluntarily checked into an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (with Theo’s money). Vincent van Gogh spent one year at the asylum in Saint-Rémy de Provence, and he painted another 150 pieces. It was the most challenging year of his life, but it would also prove to be one of his most creative. It was here, in between psychotic episodes including eating his paints, that he created his masterpiece “The Starry Night”.

“The Starry Night” (1889)

“The Starry Night” (1889), a stylized version of the nighttime sky in motion over the countryside near the asylum, is to me the greatest painting of all time. It was painted in the daytime using Gauguin’s method of painting from imagination. It hangs on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and during a recent visit it was the first painting I had to see. I stood there awestruck hoping Vincent was looking down from heaven to see how many people loved it and him. The sky was painted with ultramarine and cobalt blue, and the stars and the moon were painted with Indian yellow together with zinc yellow. To me, it’s as if van Gogh had super vision – he could see things that a normal human can’t. Most people would say the night sky is black but to Vincent it was dark blue. He saw the constantly moving streams of light that surround each star. He could see the stars moving across the backdrop of The Milky Way. He could see the clouds moving over the mountains at night. He could see them in his mind and in his heart. I have no idea how he did it.

“The Starry Night” is a vision. A beautiful vision of a picturesque village nestled below the hills over which the sky above is ablaze with spectacular beauty. Van Gogh was the absolute definition of the typical “tortured artist” – a man plagued with dark demons that grew over time out of periods of sadness, depression, loss, and unrequited love. But he took this darkness and twisted it into works of beauty and joy that celebrated life and the beauty and wonder our world. (I always wanted to do that.)

In May 1890, van Gogh left the asylum and moved closer to Theo in the Paris suburb of Auvers-sur-Oise and under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet. In Auvers, he was often happy spending his days in the surrounding wheat fields painting a piece almost every day, however, his new neighbors found the deformed eccentric to be a madman just like in Arles. In July, Van Gogh wrote that he had become absorbed “in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow”. Theo had recently married a woman named Jo Bonger and had a baby that they named Vincent. During his time at Auvers, van Gogh became riddled with guilt over living off his brother, now especially because Theo had a wife and baby to support as well. In July, van Gogh described the wheat fields to Theo as “vast fields of wheat under turbulent skies”.

On July 27th, at age 37, van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a pistol. There were no witnesses and he died 30 hours after the incident with his faithful brother Theo by his side who once again rushed from Paris to help. Some believe that Vincent did not commit suicide but was shot accidently by a teenager who lived in the village and was known to carry a small gun. If Vincent had planned to kill himself (with a gun he supposedly stole from an innkeeper) why did he haul his easel, paints, brushes and canvas a mile down the road to paint in a wheat field? Why was the gun and his paint supplies never found? Why shoot himself in the chest and not in the head? After the first shot failed to kill him, why not shoot again? Why did the doctor who first examined him claim that his wound suggested the shooter was far away? Why would such a religious person commit the sin of suicide? We’ll never know the answer to these questions. I believe that Vincent was accidently shot by the teenager but once wounded, he had finally found a way to put things right. He would die, his pain would end, Theo would be free of his financial burden and perhaps, once dead, his paintings would increase in value and Theo could sell them and pay himself back for all the money he “loaned” to Vincent.

The true hero of this story is Jo Bonger. Weak and unable to come to terms with Vincent’s death, Theo died six months later at age 33. After Theo’s death, Bonger took it upon herself to honor both brothers. She edited all the brothers’ letters to each other into a book, producing the first volume in Dutch in 1914. The book remains a popular seller to this day. She also played a key role in the growth of Vincent’s fame and reputation through her donations of his work to various early retrospective exhibitions and holding exhibitions herself. If there was no Jo Bonger, we would’ve probably forgotten about Vincent and “The Starry Night” wouldn’t be hanging in the Museum of Modern Art. After his 63 days in Arles with van Gogh, Paul Gauguin turned his back on Western society and eventually moved to Tahiti where he painted the natives and became a major figure of Post-Impressionist and Symbolist art. He is now recognized for his experimental use of color and his major influence on Fauvist art. His life is forever linked with van Gogh’s. The two men would never see each other again in person, although they continued to write each other letters right up until van Gogh’s death in 1890. Gauguin died in 1903. Vincent and Theo are buried side-by-side in a cemetery in France.

-

Pablo Picasso

(25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973)

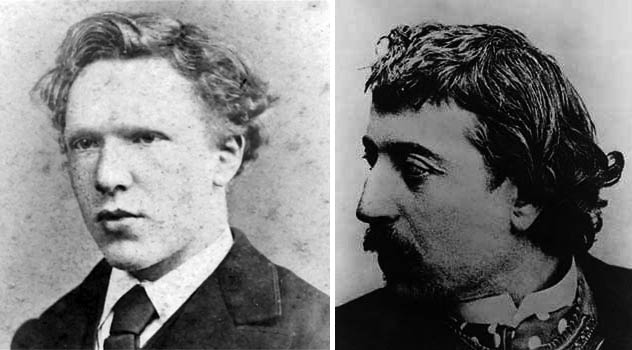

Pablo Picasso lived his life on a higher plane of existence than normal humans. Straight up. He was a highly evolved, highly advanced human being. The word “genius” is thrown around a lot these days, but he truly was one. He was the greatest artist the world has ever seen. There will never be another Picasso. Never. He did it all – he was a painter, sculptor, printmaker and ceramicist.

Pablo Picasso lived his life on a higher plane of existence than normal humans. Straight up. He was a highly evolved, highly advanced human being. The word “genius” is thrown around a lot these days, but he truly was one. He was the greatest artist the world has ever seen. There will never be another Picasso. Never. He did it all – he was a painter, sculptor, printmaker and ceramicist.

The artistic genius of Pablo Picasso has impacted the development of modern art for decades leaving an artistic legacy that continues to resonate today throughout the world. His prolific output includes over 20,000 paintings, prints, drawings, sculptures, and ceramics that convey a range of intellectual, political, and social messages. His work will live forever. If you ask 100 people on the street to name one famous artist, I am confident the majority will say one word – “Picasso”.

Born in Spain, Picasso was a child prodigy who showed great skill and passion for drawing at an early age. His mother claimed his first word was “piz”, an abbreviation of the Spanish word for pencil. His father was an art teacher and began formally training him in figure drawing and painting at age seven. Seven! When I was seven, I spent my days watching Batman and The Monkees on television. Pablo at that age was copying famous works by Renaissance masters and drawing the human body from live models.

Regarded as the most influential artist of the 20th century, Picasso spent most of his adult life in France. His life was the exact opposite of Vincent van Gogh’s. Picasso became famous. World famous. He could walk into a restaurant and buy a meal with a doodle on a napkin. (I always wanted to do that.) He had numerous homes filled with priceless works of art (some his, some by others that he collected) including gigantic mansions and beach houses along the French Riviera. He was a ladies’ man and had many (many!) female admirers. (He was known to walk up to pretty ladies and say, “Excuse me, I am Picasso, and I would love to draw your portrait.”) He was beloved, recognized as a genius and was one of the richest men in the world. Vincent also lived his life in France but sadly, without any of these things.

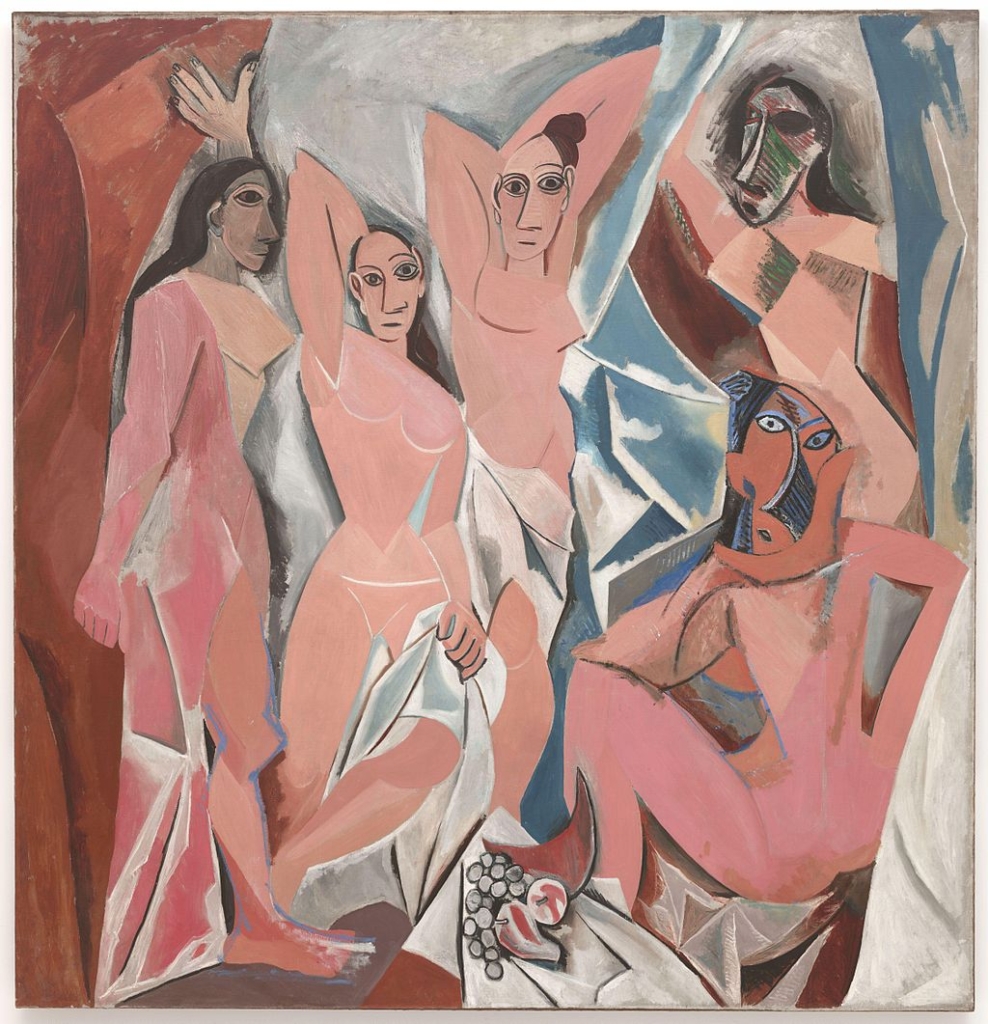

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907)

Among all his celebrated achievements, Picasso may be best known for inventing Cubism. Highly influenced by African art, he also contributed to the rise of Surrealism and Expressionism. His 1907 painting “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (The Young Ladies of Avignon) is the perfect example of these genres. It hangs in the Museum of Modern Art where I’ve seen it and studied it up close many times. The painting has had an enormous and profound influence on modern art. Some have said it is one of the most shocking paintings of all time. It’s not just a painting but an experience – a confrontational encounter. The viewer walks into a brothel and comes face to face with five menacing prostitutes. Everything in the painting is dangerously sharp and strangely flat. The two figures on the right wear African masks which convey an ethnic primitivism that according to Picasso, moved him to “liberate an utterly original artistic style of compelling, even savage force.” “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was revolutionary and controversial. As a radical departure from traditional painting, it led to widespread anger and disagreement, even amongst the painter’s closest friends. It wasn’t shown publicly until 1916 and was not widely recognized as a revolutionary achievement until the early 1920s. I have no idea how he did it.

Fauvist painter Henri Matisse, a more established painter at the time, considered the work something of a bad joke and was reported to be fighting mad upon seeing it inside Picasso’s studio. Matisse felt that Picasso was attempting to ridicule the modern movement. Henri Matisse’s vibrant color palettes, expressive brushstrokes, and flat, graphic forms helped define the aesthetics of Fauvism and Modernism itself. Matisse was Picasso’s lifelong creative rival.

Picasso and Matisse were both greatly influenced by Paul Cezanne (who would come in at #5 on this list if I wasn’t so lazy) and spent their careers attempting to one-up each other. As the two artists’ rivalry grew, so did a mutual respect. Although their rivalry made for a tense friendship, the constant competition pushed each painter further than they would have gone on their own. In the autumn of 1907, Matisse and Picasso had agreed to swap paintings. Each selected what he considered the worst example of the other’s new work, as if to reassure themselves. Picasso picked a portrait of Matisse’s daughter, and Matisse chose a still life. It was said that Picasso hung the Matisse in a room where he threw darts at it.

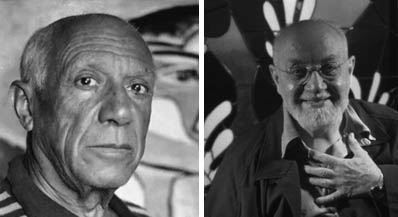

Pablo Picasso, left, and Henri Matisse.

“Only one person has the right to criticize me,” said Matisse. “It’s Picasso.” Matisse died in 1954. Picasso once said, “If I were not making the paintings I make, I would paint like Matisse. In the end, there is only Matisse.” Picasso died in 1973.

-

Willem de Kooning

(24 April 1904 – 19 March 1997)

Willem de Kooning is my idol. He’s the guy I want to be. His career is the one I want to have. I think he’s just the coolest – an artist who plays by his own rules. An “artist’s artist”.

Willem de Kooning is my idol. He’s the guy I want to be. His career is the one I want to have. I think he’s just the coolest – an artist who plays by his own rules. An “artist’s artist”.

Willem de Kooning is one of the most important artists of the 20th century. He was born in The Netherlands, lived in a poor household, and trained in fine and commercial art at the Rotterdam Academy. In 1926, he basically said, “Screw this!” and stowed away on a steamship bound for the US. When it came to going through the proper immigration channels, he basically said, “Screw this” and lived illegally in New Jersey as a house painter. Dreaming of an even better life in New York City, he basically said, “Screw this” and moved to The Big Apple in 1927 and began his painting career. Seeing a pattern yet?

He lived in a very small studio on West 44th Street and visited art galleries in his spare time. New York brought him into contact with the work of Picasso and Matisse and he became close friends with abstract artist Arshile Gorky who served as his mentor. During the Great Depression, de Kooning, like a lot of his fellow Big Apple artists, was employed in FDR’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, where he designed murals. In 1937, however, he had to leave the WPA because he did not have American citizenship and it was then that he basically said, “Screw this” and began to work full-time as an artist.

By the 1940s, de Kooning had begun to gain prominence as a respected artist and later became one of the most prominent of the New York Abstract Expressionist painters – a small group of loosely affiliated artists that created diverse styles that introduced radical new directions in art and shifted the art world’s focus from Paris to The Big Apple. Willem de Kooning’s pictures typify “action painting” – the strong, gestural style of this exciting new movement. Using his experience as a house painter, where large brushes and enamel paints were the tools of the trade, he developed a style of painting that fused Cubism and Expressionism. In the 1950s, when other “action painters” such as Jackson Pollock (we’ll get to him in a bit) were moving toward pure abstraction, de Kooning developed a signature style that fused vivid color and aggressive paint handling with disturbing, violent representations of the female form. Abstract and representational at the same time.

“Woman I” (1950-52)

Take for example, his most famous painting “Woman I” (1950-52), a painting that de Kooning abandoned many times (“Screw this”) and once had to be rescued from a dumpster by a fellow artist who saw its great potential. He executed numerous preliminary studies before beginning the painting, started over several times, and worked on it in stages over three years that involved the creation and destruction of many other possible versions.

“Woman I” now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art and the last time I was there I spent almost a half hour staring at it. I got as close as I could and stared at small sections of it wondering to myself how he achieved such a masterpiece. It’s like hundreds of little paintings inside one giant painting. I have no idea how he did it.

“Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented,” de Kooning once remarked. Some of his contemporaries who were devoted to pure abstraction saw the painting as a betrayal, a regression to an outdated figurative style. Others called it misogynistic, interpreting it as objectifying to women. De Kooning himself said, however, “Beauty becomes petulant to me. I like the grotesque. It’s more joyous.” De Kooning’s prized experimentation and editing. He used a variety of techniques, from cutting, masking, collaging, and scraping. His purposefully undisciplined brushwork produced a visual chaos that suggests incompletion. “I refrain from finishing,” the artist said in 1958.

By the late fifties, he had moved from women to women in landscapes in what seemed to be a return to “pure” abstraction, with works respectively referred to as “Urban,” “Parkway” and “Pastoral” landscapes. In 1959, he had his most successful show ever. Held at The Sidney Janis Gallery, he exhibited 22 of these new paintings and sold 19 of them by lunchtime making him a very rich man. (I always wanted to do that.) “The landscape is in the woman, and there is woman in the landscapes,” said de Kooning.

In 1963, he left the noise and dirt of New York City for the sunshine and water of The Hamptons and designed himself a huge expensive barn-like studio next to his new house in Springs, NY. It’s basically, the coolest studio ever built in one of the nicest neighborhoods at the tip of Long Island. It was a very long way from his impoverished life in The Netherlands. De Kooning’s rival Jackson Pollock lived in the same neighborhood and de Kooning visited the area many times in the 1950s.

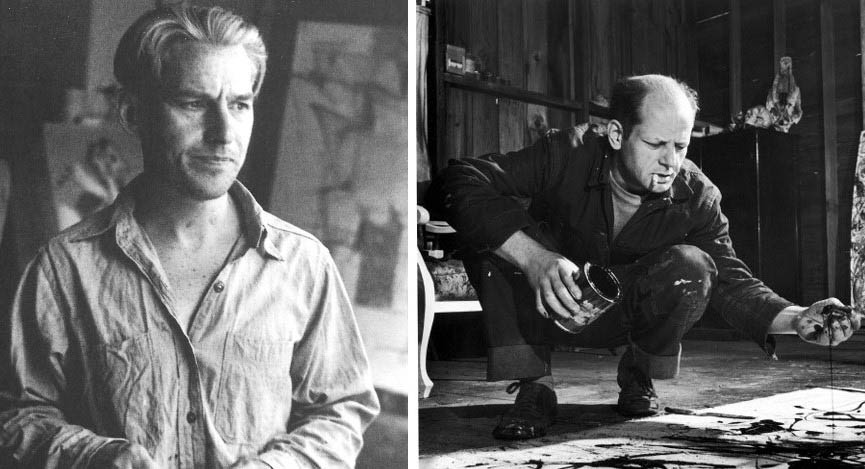

Jackson Pollock was a titan of Abstract Expressionism, another “action painter” and one of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. He invented a process which produced very large, gestural, all-over “drip paintings”. De Kooning, who called Pollock “the painting cowboy”, was charmed by the younger man’s outlandishness and his sense of freedom but both vied to be perceived by his peers as the leader of Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock was THE public face of the New York avant-garde and de Kooning was described as second in command. Both men were also serious alcoholics.

Willem de Kooning, left, and Jackson Pollock.

The rivalry between de Kooning and Pollock and was also driven by two argumentative critics, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. The two intellectuals had a huge influence on the artistic community at the time. Greenberg championed Pollock, who perfectly encapsulated his ideals of modernist work with abstract, flat paintings. Rosenberg, a more existential critic, backed de Kooning’s paintings, which were alive with thick strokes of paint.

Both artists were also married to other artists – Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner Pollock – and both had affairs with other women. In the last months of his life, Jackson Pollock, fell in love with a younger woman named Ruth Kligman. She was the only survivor of the car crash that killed Pollock and another friend. Within a year de Kooning said “Screw this” and began his own relationship with Kligman, which lasted seven years. In 1963, when De Kooning moved to his new house in The Hamptons, it was opposite the cemetery where Pollock is buried.

After Pollock’s death, de Kooning had become the leader of the Abstract Expressionists. He went on to get his American citizenship, stopped drinking, and painted into his eighties until illness prevented him from continuing. He was the longest living of the Abstract Expressionists. The one thing he never gave up was his art – he never said “Screw this” to that. De Kooning died in 1997. Pollock was killed in a car crash while drunk in 1956.

-

Francis Bacon

(28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992)

Every first-year art student is inevitably asked to pick a painter, usually from an art history textbook (or nowadays an art history website) and do a painting in their style for an art assignment. The assignment was not to copy their style but to be influenced by it and create something similar with the same tone and emphasis. When I was asked, I went to the University of Delaware library and looked through an art history textbook (there was no internet in the mid-1980s) and began to thumb through the pages. There was one painter that stopped me in my tracks and I became excited, repulsed, fascinated, and intrigued by what I saw. “Who the hell is this?!” was probably what went through my mind. The work of this Irish-born 20th century painter had suddenly attached itself to my eyes and absorbed itself into my brain like an alien entity. It’s lived there ever since. His work haunts me.

Every first-year art student is inevitably asked to pick a painter, usually from an art history textbook (or nowadays an art history website) and do a painting in their style for an art assignment. The assignment was not to copy their style but to be influenced by it and create something similar with the same tone and emphasis. When I was asked, I went to the University of Delaware library and looked through an art history textbook (there was no internet in the mid-1980s) and began to thumb through the pages. There was one painter that stopped me in my tracks and I became excited, repulsed, fascinated, and intrigued by what I saw. “Who the hell is this?!” was probably what went through my mind. The work of this Irish-born 20th century painter had suddenly attached itself to my eyes and absorbed itself into my brain like an alien entity. It’s lived there ever since. His work haunts me.

Francis Bacon’s macabre portraits express the widespread anxieties of post-war Europe and the artist’s own personal demons. He painted screaming abstracted faces, pieces of animal meat, crucifixes, and howling popes in claustrophobia-inducing settings (usually transparent boxes or cages), with ominous and discomfiting palettes of pinks, whites, reds, and blacks. He is known as a uniquely bleak chronicler of the human condition who strove to render “the brutality of fact”. He built up a reputation as one of the giants of 20th century art with his unique figurative style. (I always wanted to do that.)

Look at his grotesque “Painting” (1946), also known as “the butcher shop picture”, to get the drift of what I’m talking about. The Museum of Modern Art has this disturbing painting in their collection, and I’ve seen it in person. Their website describes it as such: Created in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Painting is an oblique but damning image of an anonymous public figure. The umbrella that partially obscures him might refer to Neville Chamberlain, the prewar British prime minister who was known for carrying one. His dark suit—the unofficial uniform of British politicians of the day—is punctuated by an incongruous bright yellow boutonniére, yet his deathly complexion and toothy grimace suggest a deep brutality beneath his proper exterior. In the background, three window shades evoke those found in an often-circulated photograph of Hitler’s bunker, an image the artist included in multiple works. The sense of menace is accentuated by glaring colors and the cow carcasses suspended in a cruciform behind him, a motif drawn from Bacon’s childhood fascination with butcher shops, but also a possible reference to Old Master treatments of the same subject.

“Painting” (1946)

Bacon described the work as his most unconscious. “It came to me as an accident,” said Bacon. “I was attempting to make a bird alighting on a field. And it may have been bound up in some way with the three forms that had gone before, but suddenly the line that I had drawn suggested something totally different and out of this suggestion arose this picture. I had no intention to do this picture; I never thought of it in that way. It was like one continuous accident mounting on top of another.” When I look at this painting, I often say to myself “What in the hell was going on in this guy’s mind?” and then I realize that it must be literally hell. I have no idea how he did it.

Bacon was named after his distant relative Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the famous English Renaissance statesman and philosopher best known for his promotion of the scientific method. The 20th century Bacon was a tortured homosexual (homosexuality was illegal in Britain until 1967) who would often become involved in extremely violent, yet consensual, sadomasochistic relationships with men. He was charismatic, articulate, and well-read. He was an obnoxious heavy drinker, a voracious eater, and a degenerate gambler.

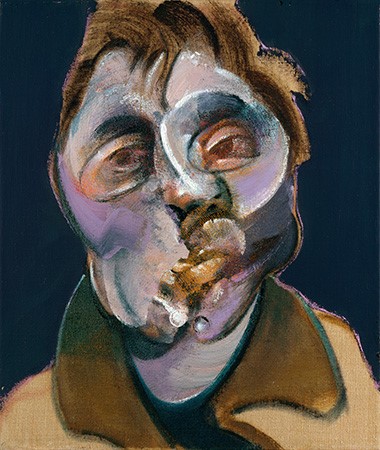

His contemporary rival was Lucian Freud, one of the most important figurative painters of the past century. The grandson of Sigmund Freud, the artist became famous for his unflattering, disturbing paintings of the nude human body. Bacon and Freud had famously befriended each other in London in the 1940s and became good friends (aka drinking buddies). As two figurative artists working at a time when abstraction was the pervading fashion (see de Kooning above), they constantly scrutinized each other’s work, offering comments and criticism. “Francis opened my eyes in some ways,” said Freud. “His work impressed me, but his personality affected me.”

I saw an exhibition of Freud’s paintings in the fall of 1987 at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C. The Hirshhorn was the first North American venue for a major retrospective by Freud and on view were 70 of his paintings and 14 of his drawings, chosen by the artist. It was amazing to say the least. His style of portraiture is instantly recognizable, and his fleshy nudes and self-portraits are incredible to view up close.

Francis Bacon, left, and Lucien Freud.

Although they were painting in the same tradition, Bacon and Freud’s ways of working couldn’t have been more different which made for a volatile and combustible mix. But by the 1970s their relationship had completely unraveled and the two stopped speaking. Even a decade after Bacon’s death, it was considered taboo to broach the subject with Freud during interviews. Some art historians believe the relationship eventually ended because of Freud’s jealousy of Bacon’s talents and celebrity status and Bacon’s rejection of Freud’s social climbing snobbery.

Bacon famously sat for three months as Freud painted his portrait in 1952. Mesmerizing and memorable, the painting expertly represents Bacon’s volatile (and often sad) nature. Unfortunately, the portrait was stolen right off the wall at an exhibition in Berlin in 1988. Freud later designed a “wanted” poster for his missing painting and posted them around Berlin in the hope that it would be found, but it has never been recovered. Someone out there somewhere has it. Someone out there selfishly has stashed the most important document of this famous friendship that came to its sad, and eventual, conclusion. Bacon died in 1992. Freud died in 2011.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Psychological scientist Gavin Kilduff of New York University found that people report higher performance when competing against their rivals. Kilduff argues that interpersonal relationships have a huge impact on motivation, which explains why rivalries increase performance and creativity. None of the artists on my short list hated their rival, they were probably very grateful and thankful for their rival. Having a rival and embracing good tension, can eventually help you in your performance. Healthy rivalry can make you more creative. So, that IS how they did it.

By the way, this blog post is 5,863 words long. How did I do that?